You know I love a challenge.

It’s going to be harder to write during the summer months, with boys underfoot and trips to here there and everywhere (bonjour, Bretagne!), so I’m going to spend my summer months feeding the creative monster.

I’ve been finding it hard to write recently, partly because my brain is begin pulled in fifteen different directions. I’m feeding it with information — about education, about fitness, about nutrition, about cognitive behavioural therapies, about music, about all kinds of practical stuff — but I’m not feeding it with the kinds of stories it needs to lift itself out of the everyday world and into the world of stories.

So I’m going back to the Bradbury Method of creativity-boosting. I did this last summer and it worked like a charm: I read a new story every day (and an essay and a poem as often as I could manage that) and found myself drowning in ideas. I had a burning urge to write; I sketched out ideas for stories; I wrote some of them over the next six months and released them as Kindle ebooks that have sold actual copies and generated actual profits. I have others that are still in various stages of drafting. But more than all that I was happy.

Follow Along?

So that’s what I’m going to do: Read and log as many short stories as I can this summer. I’m logging my activity at my personal reading log and you can do the same.

Your Own Reading Log

I’m using Google Docs to log my reading.

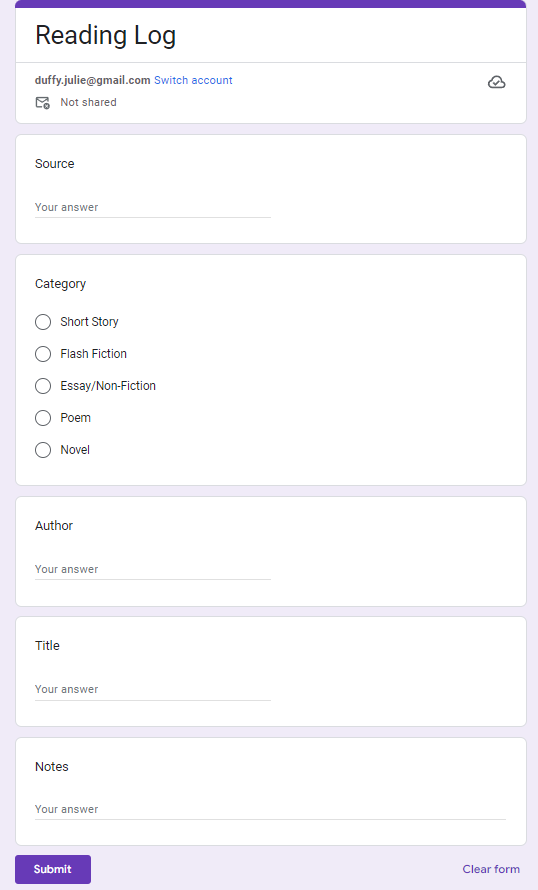

Here’s a copy of the form that you can use yourself if you want to join in and you like Google Docs. Save a copy of this form to your own Google Drive and rename it.

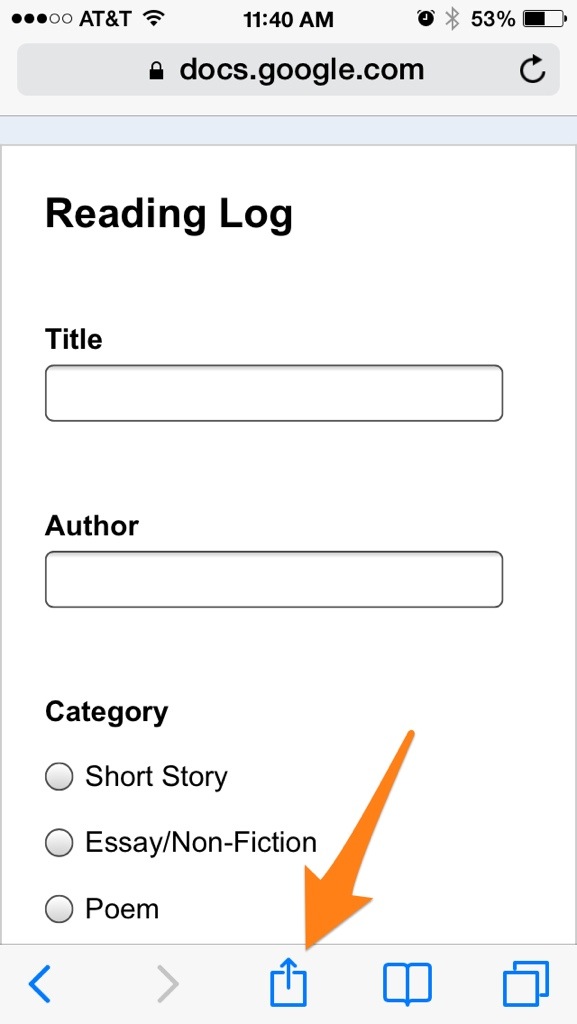

If you click on “Tools/Create New Form you can create a Google form, which i find to be a nice, clean interface for entering info. It’ll update the spreadsheet automatically (no silly little cells to click on).

Here’s a screenshot of my form, for reference.

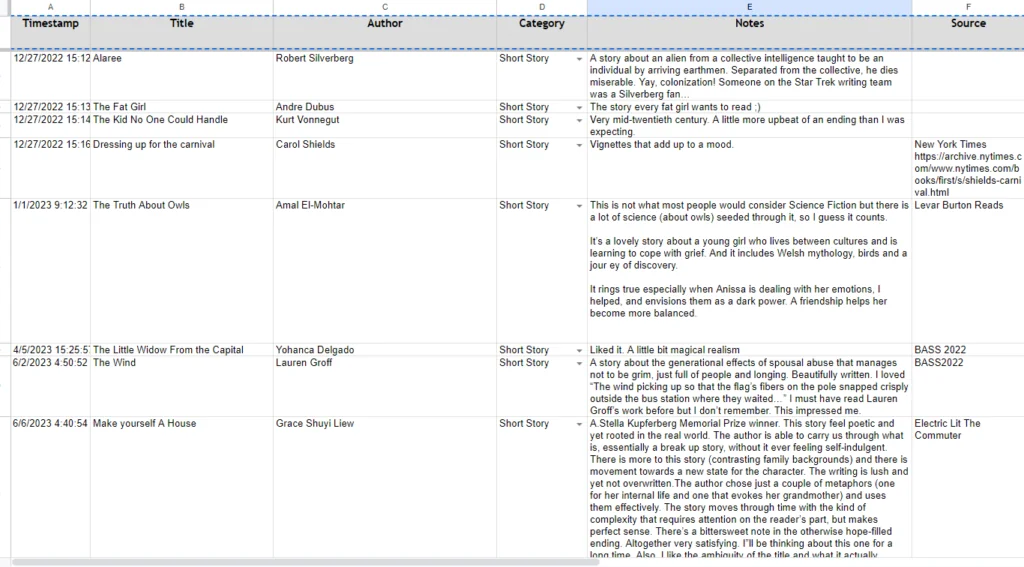

…and here’s how my ugly-but-useful spreadsheet looks:

Bonus Tip: Create A Handy Shortcut

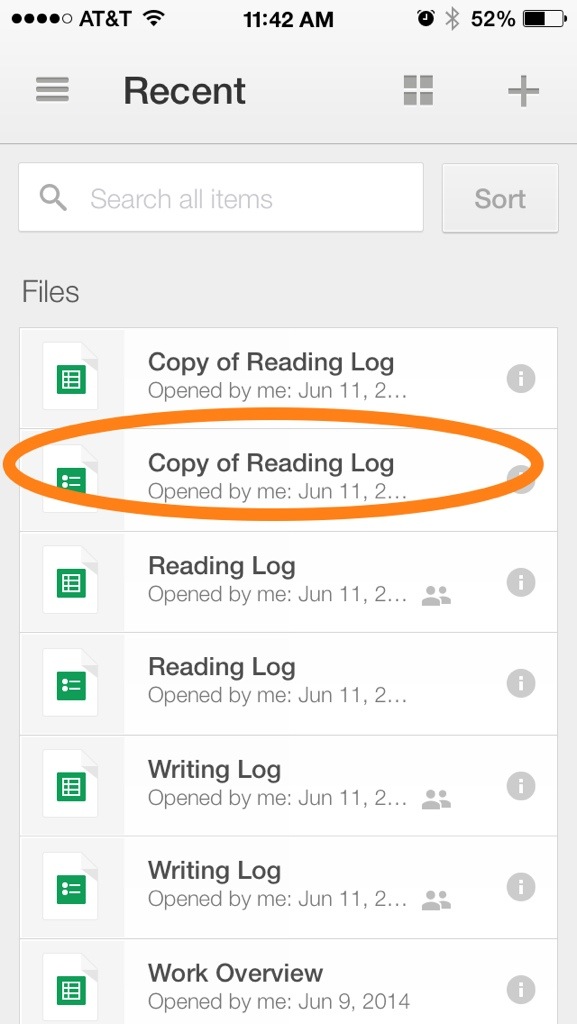

If you’re an iPhone user, you can follow these steps to get an app-like link on your phone, to make logging your reading easier (I’m a big fan of ‘easy’)

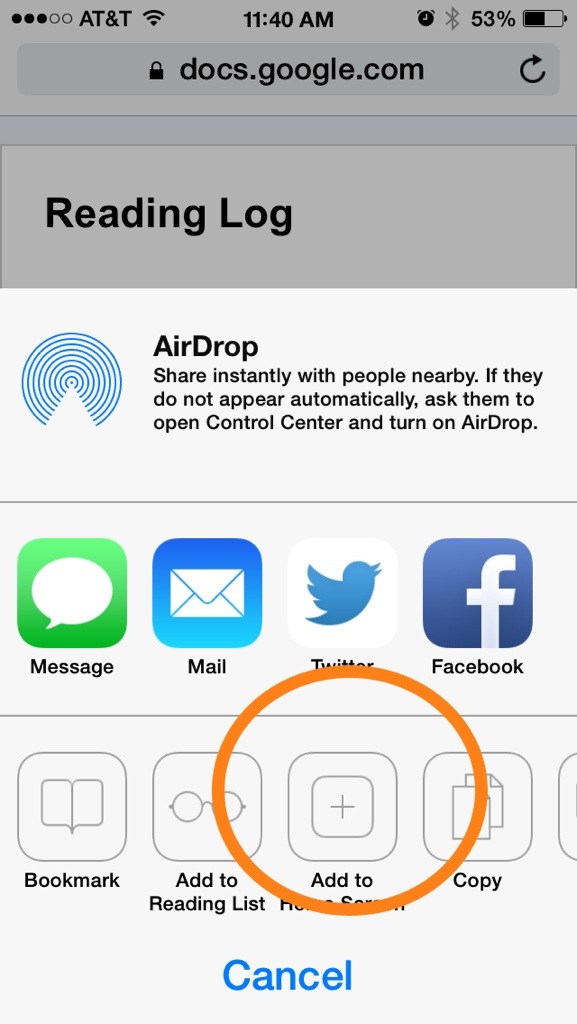

Step 1:

Go to your form on in your browser (drive.google.com/)

Then:

Then

Then

How it looks on your phone:

Voilà!

Just make sure you save a copy of this document to your own Google Drive and don’t send me an email requesting permission to edit this copy, OK?