Opening lines are hard to write because they have to do so much:

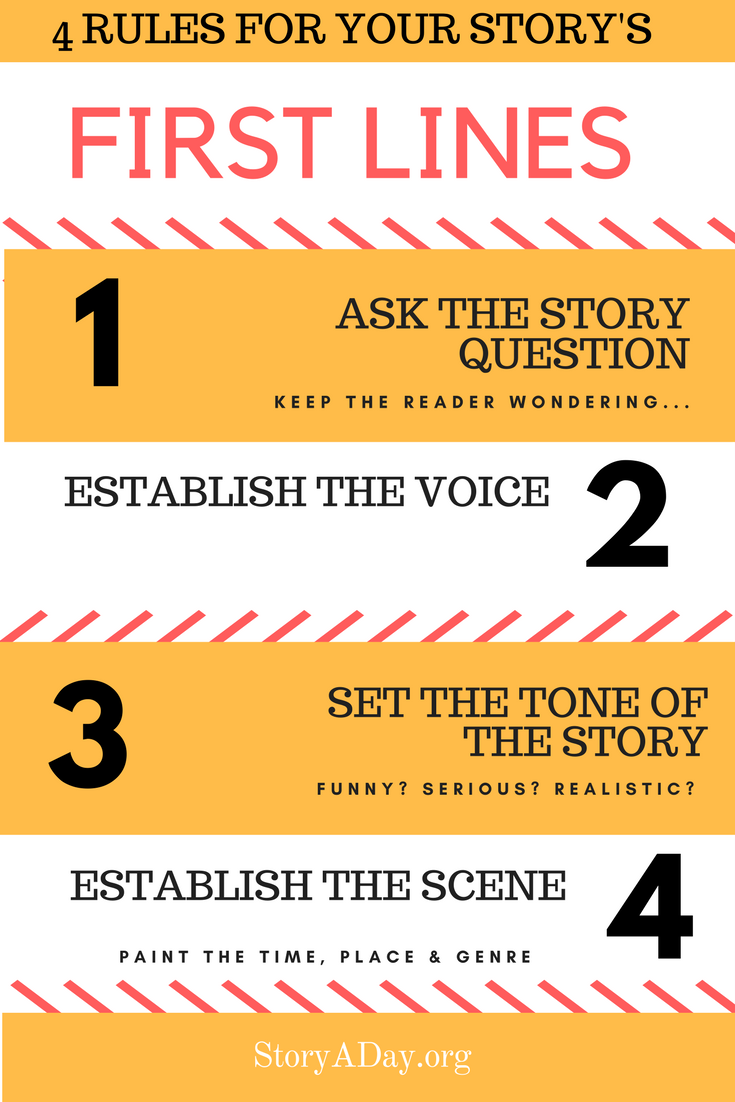

What Opening Lines Must Do:

- Set up the main question the reader is going to be asking all the way through

- Establish the voice of the protagonist/narrator

- Set the tone

- Ground the reader in a time or place

That’s why I advocate writing the first lines last—or at least tweaking them after you’ve finished the story, when you know what it’s about.

So, how do you make your first line reflect all these things?

Let’s look at some examples.

four update: seven of the stories.

Maidencane – Chad B. Anderson

Nowadays the memory starts like this: there’s a rush in the red dirt, and you and your brother snatch up the tackle box and run from the girl. She flings her fishing pole at you and yells that her daddy will just buy her another tackle box. And another, and another. The girl’s echoes follow you along the riverbank.

This opening paragraph sets the story firmly in the narrator’s voice: which, in this case, is second person. It’s still a relatively unusual point-of-view but I’m seeing it more and more, especially in short stories. I think it gives the story an immediacy it might otherwise lack, and draws the reader in. It also introduces the prospect of the narrator being unreliable. They’re holding us at arm’s length, not saying “I did this” but “say, you did this”.

(I always feel like there’s an unspoken “hypothetically…” in a second-person story. I kind of like it.)

“Nowadays” – implies that something has changed over time. This pulls the reader in, asking a question that they expect to find the answer to, before the end of the story.

This kind of question will hook the reader and keep them reading until you answer it. (At which point, I hope, you’ve asked another question to keep them reading.)

“The memory starts” – this invites the reader to ask more questions: why are we hearing about a memory? Why not just talk about the memory with the other participants in the scene? Where are they now? What is going to be significant about this memory.

Remember: short story readers are puzzle-solvers. They know every detail in a short story is there for a reason and they enjoy tallying them up, trying to unpick the story puzzle as they read. Don’t frustrate them by throwing in things that waste their time and mental energy!)

“A rush in the red dirt” – This language is non-obvious. What does it mean? It slows the reader down as they try to make sense of it. It sets the tone for the story: it’s going to be literary. It also raises questions in the reader’s head. This time the question is answered quickly: the rush is a girl. In telling us that, the writer immediately raises more questions: they are running from the girl. Why? Who is she? What will the consequences of this interaction be, for the characters and the story?

“She flings the fishing pole at you” – this is wonderful example of showing, not telling: she doesn’t “throw the pole, angrily”. She flings it. It’s the perfect word. It is active. It invites the reader to see the scene and to wonder what came before, and what will come after. You want to keep reading, don’t you?

“Her daddy will just buy her another” – we can hear the defiance in the girl’s voice, but the writer doesn’t tell us too much, too soon. We don’t know if it’s true, or why he mentions this. Is her daddy rich? Is she spoiled? Is she proud and faking it? What is going on, here?!

Following directly on from this paragraph, the writer slows things down a bit, describing the scene and shifting the mysteries from the question he’s raised about the girl, to new questions about the brother (“you wish you could remember the songs he liked” — why can’t you just ask him?)

This paragraph sets up much that the story will be about: it turns out to be about memory and consequences, and relationships.

While the girl in the opening does turn up again throughout the story (in a way), the story pivots to one about the narrator’s family, her relationship with her brother. But it is also a story about memory and consequences.

All these things are in the opening, along with questions the reader wants answered, a strong sense of voice and place, and action that pulls us into the story.

It’s a strong opening.

How To Fix Your Own Opening Lines

Now that you’ve seen what a great opening can do, are you looking at your own stories with a twisted expression on your face?

Don’t panic! You can make your openings stronger with a few quick tweaks.

- Read over your story and think about the major theme that emerged. Find a way to raise a question about that theme in the opening few lines. For inspiration, look read “Maidencane” by Chad B. Anderson in The Best American Short Stories 2017.

- Use language that strongly illustrates your character’s voice and personality. For inspiration read “Are We Not Men?” by T. C. Boyle.

- Set the tone for the story by concentrating on how your opening lines might make the reader feel. For (uncomfortable) inspiration, read “God’s Work” by Kevin Canty.

- Ground your story in a time and place, without resorting to telling us where it takes place. For inspiration read “A Small Sacrifice for an Enormous Happiness” by Jai Chakrabarti.

What would you add? Leave a comment.